Sheikh Ayesha Islam

Indian cinema has often been described as a mirror to society, sometimes reflective, sometimes critical. But that description feels increasingly inadequate. A section of contemporary Hindi cinema is no longer interested in reflecting reality. It seeks to define it. Films now arrive packaged as revelations, hidden truths finally exposed, suppressed histories courageously told. They do not invite viewers to interpret what they see; they urge them to accept it as fact. This shift is not merely cinematic. It is political. It concerns who gets to narrate history, whose suffering is amplified, and which community is made to stand in as the permanent enemy within.

To understand what has changed, it is useful to distinguish between representation and assertion. Representation carries an awareness of mediation. It accepts that cinema interprets reality through perspective, selection, and limitation. Assertion rejects that humility. It presents its narrative as closure, the final word on what happened and who must be blamed. Much of Indian cinema today operates in this assertive mode, replacing inquiry with certainty and complexity with accusation.

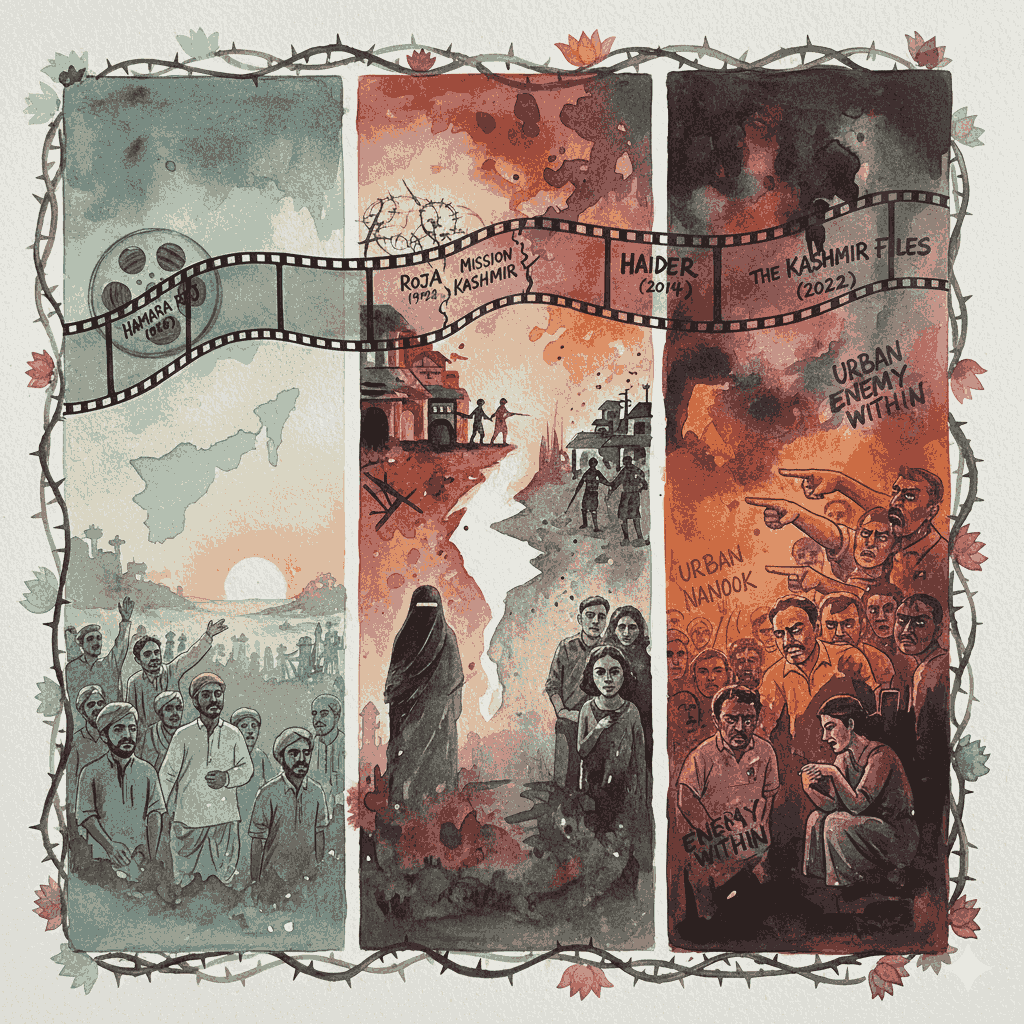

Early Indian cinema functioned very differently. Emerging under colonial censorship, uneven literacy, and tightly policed political speech, films were not investigative projects. They were emotional worlds designed to produce coherence. Productions like Alam Ara relied on melodrama, song, and mythological frameworks to organise social life into recognisable moral orders. Hierarchies were aestheticised, gender roles stabilised, and suffering moralised rather than politicised. Structural injustice appeared as fate, not design. Yet even within these ideological limits, cinema did not claim historical authority. Fiction remained fiction. Audiences were offered meaning, not manufactured truth.

The ethical possibilities of representation expanded most powerfully with filmmakers like Satyajit Ray. Ray’s cinema did not declare reality; it observed it. His films resisted emotional coercion and narrative simplification. Poverty appeared with context rather than spectacle. Power was embedded in institutions and social habits, not condensed into villainous figures. Characters were contradictory, fragile, socially located. Silence was allowed space. Music did not instruct viewers what to feel. This ethic of restraint extended through the work of actors such as Smita Patil (Manthan), Naseeruddin Shah (Aakrosh), and Farooq Sheikh (Chashme Buddoor), whose films examined caste, labour, gender, and political fatigue without moral absolutism. This cinema trusted audiences to think. Its marginalisation came alongside an industry increasingly shaped by box office urgency and, later, algorithmic visibility that rewards emotional immediacy over reflective storytelling.

As realist traditions receded, mainstream cinema developed another strategy, translating structural conflict into personal antagonism. Films like Sholay, or later vigilante narratives, transformed systemic injustice into battles between heroes and villains. Institutions disappeared behind individual evil. Justice arrived through masculine retribution rather than social accountability. Audiences experienced catharsis, but not analysis. Yet even then, these films did not insist they were revealing suppressed historical truths. They dramatised conflict without claiming documentary authority.

That boundary has eroded sharply over the last decade. A cluster of films has repositioned itself not as storytelling but as truth-telling. The Kashmir Files and The Kerala Story were promoted as necessary revelations, films audiences were told they “needed” to watch in order to understand what had supposedly been hidden from them. Marketing campaigns, political endorsements, and media amplification reinforced this framing. These films did not arrive as interpretations; they arrived pre-authorised as truth.

Within this narrative universe, Muslims are rarely depicted as historically situated citizens. They appear instead as conspiratorial actors, demographic threats, ideological infiltrators, or civilisational enemies. Selective incidents are scaled into community character. Individual violence is reframed as collective design. Counter-histories disappear. Political contexts dissolve. What remains is a morally compressed universe in which fear feels historically justified.

Read More: Ikkis: A Journey Through Memory, Conscience, and the True Cost of War Across Two Timelines: Manufacturing Memory: Nationalism, Fear, and the New Politics of Hindi CinemaThe distortion here does not always lie in inventing events wholesale. It lies in selection and compression. Timelines are collapsed to imply inevitability. Complex conflicts are stripped of reciprocity. Institutional failures are reassigned to communal malice. The past is reorganised into a grievance narrative aligned neatly with present nationalist anxieties.

Cinematic form plays a crucial role in manufacturing this emotional certainty. Background scores surge before evidence appears, instructing viewers how to feel in advance. Editing produces conspiratorial continuity where none exists. Lighting codes menace and victimhood. Silence, which might allow doubt or reflection, is minimised. By the time narrative claims unfold, viewers are already affectively aligned. Emotion precedes judgment.

These films often resolve in nationalist closure. The nation appears wounded but righteous, betrayed by internal enemies yet redeemed through exposure. In this moral geography, Muslims are positioned as suspect citizens, present within the nation but narratively outside its moral core. Nationalism becomes both emotional resolution and ideological instruction.

The warnings of George Orwell feel particularly relevant here. Orwell wrote that the ultimate power of propaganda lies not simply in falsehood, but in defining what counts as truth, collapsing the distinction between repetition and reality. Contemporary assertion cinema operates in precisely this space. It does not investigate; it declares. It does not contextualise; it compresses. Dissent is framed as denial. Historical debate becomes moral betrayal.

Cinema’s impact is magnified by the media ecosystems through which it travels. Film scenes circulate through television debates, political speeches, and social media networks. Dialogues become evidence. Fiction migrates into public memory. Repetition produces familiarity; familiarity produces belief.

The consequences are civic, not just cultural. Audiences habituated to narrative certainty lose patience with ambiguity. Complexity appears deceptive. Entire communities carry the burden of cinematic suspicion. Hatred, once dramatised, becomes normalised.

The question, then, is not whether cinema should engage with political trauma or contested history. It must. The question is how. Will it represent complexity or replace it with accusation? Will it humanise or caricature? Will it document violence or weaponise it?

Indian cinema today stands at a crossroads between representation and assertion. One tradition, exemplified by filmmakers like Ray, treats reality with humility, proportion, and ethical hesitation. The other claims authority over truth itself, manufacturing histories that amplify nationalist grievance while fabricating fear around minorities.

When cinema begins to distort reality while claiming to reveal it, its power extends far beyond entertainment. It reshapes memory, reorganises prejudice, and redraws the boundaries of belonging.

At that point, cinema is no longer merely storytelling.

It becomes a political instrument, one capable of manufacturing truth, and with it, hatred.

Sheikh Ayesha Islam is a Delhi-based writer who focuses on art, culture, politics, entertainment, digital discourse and broader social narratives. She can be reached at islamunofficial@gmail.com.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the policy of the platform.