By: Sheikh Ayesha Islam

Australia’s decision to mandate a social media ban for children under sixteen, while hailed as progressive by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and widely reported in the national and international media, is anything but a cause for celebration. It is a stark admission of failure: a concession that contemporary childhood is crumbling under the insidious weight of digital architectures explicitly engineered to exploit vulnerability.

If a high-income nation, buttressed by robust institutions and substantial resources, finds itself compelled to impose such a prohibition to safeguard its youth, then India is forced to confront a far more terrifying reality. What Australia merely fears as a coming storm, India is already drowning in. India is not simply approaching a childhood crisis; it is profoundly submerged in one.

The global scientific consensus on this issue is unified and unequivocal. The largest and most comprehensive study ever conducted on child brain development, the landmark Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, has provided irrefutable evidence that heavy digital exposure accelerates a critical process: cortical thinning. This thinning affects brain regions indispensable for foundational human capacities: attention, emotional regulation, and language processing. Cortical thinning is not a minor neurological aberration; it signals premature synaptic pruning, a structural change associated with long-term and severe difficulties in sustaining focus, controlling impulses, and processing complex information. If such neurological changes are observed even in supervised and well-resourced environments, the corresponding risks for Indian children, who navigate largely unregulated screens, highly overstimulating media, and minimal effective adult monitoring, are exponentially greater, constituting a developmental catastrophe.

This alarm is echoed by India’s own clinical experts. Dr. Shekhar Seshadri, a leading child psychiatrist from NIMHANS, has persistently cautioned that excessive screen time catastrophically disrupts the natural maturation of attention networks, effectively blunts emotional regulation capacities, and yields children who are paradoxically described as chronically overstimulated yet profoundly cognitively fatigued. The Indian Academy of Pediatrics corroborates this assessment, issuing warnings that early and unsupervised screen use is inextricably linked to severe sleep disturbance, impaired executive function, reduced cognitive flexibility, and pervasive behavioural dysregulation. These are not abstract, theoretical concerns; they are palpable developmental deficits manifesting in Indian classrooms every single day.

The developmental chain reaction is now impossible to deny. Structural cortical thinning initiates a cascade leading to attention collapse, which further exacerbates schooling struggles, is compounded by the pre-existing cultural environment of overstimulation, and ultimately funnels children into a state of digital dependency. This alarming trajectory is the direct consequence of an environment that relentlessly overwhelms the developing brain’s capacity for healthy, sequenced growth.

The typical Indian child’s digital landscape is uniquely hostile to healthy maturation. Domestic cartoon channels frequently devolve into pure sensory battlegrounds. Characterized by hyperactive protagonists, whiplash-inducing rapid-fire transitions, and grossly exaggerated visual cues, these media bombard the senses rather than constructively engaging them. A child consistently raised on such content quickly internalizes an expectation for the world to operate at an unnaturally frantic and demanding pace. Consequently, teachers across India are reporting with alarming consistency that children can no longer sit still through lessons, tolerate moments of silence, or effectively follow slow, complex, and sequenced explanations. These widespread difficulties must not be misdiagnosed as failures of discipline or motivation; they are the unavoidable neurological consequences of chronic, structural overstimulation.

By adolescence, the situation spirals into the dire. The foundational research by Twenge, Haidt, and Campbell demonstrates a robust correlation between heavy social media use and severe attention fragmentation, emotional volatility, pervasive depressive symptoms, and a drastically heightened vulnerability to social threat and anxiety. Crucially, these impacts are demonstrably more severe among children who lack robust emotional support or live with structural disadvantages. This profile places Indian children, who often endure suffocating academic pressure, rapidly shrinking public play spaces, unsafe urban environments, and critically limited emotional scaffolding, at the pinnacle of global vulnerability. For a significant number, the digital realm becomes a sought-after refuge, yet it is a refuge that actively and corrosively erodes the self.

The more severely overstimulated children become, the more powerfully seductive and indispensable algorithmic platforms appear. YouTube, Instagram Reels, intensive gaming applications, and short-video platforms are not merely innocuous entertainment alternatives. They are sophisticated attention-harvesting ecosystems meticulously engineered to bypass the very mechanisms of self-control. These platforms systematically reward impulsive behaviour, penalize patience and deep attention, and deliberately dissolve the necessary boundary between constructive leisure and pathological dependence. India’s continued refusal to implement meaningful regulation over these systems is not a stance of neutrality; it is an act of national abandonment.

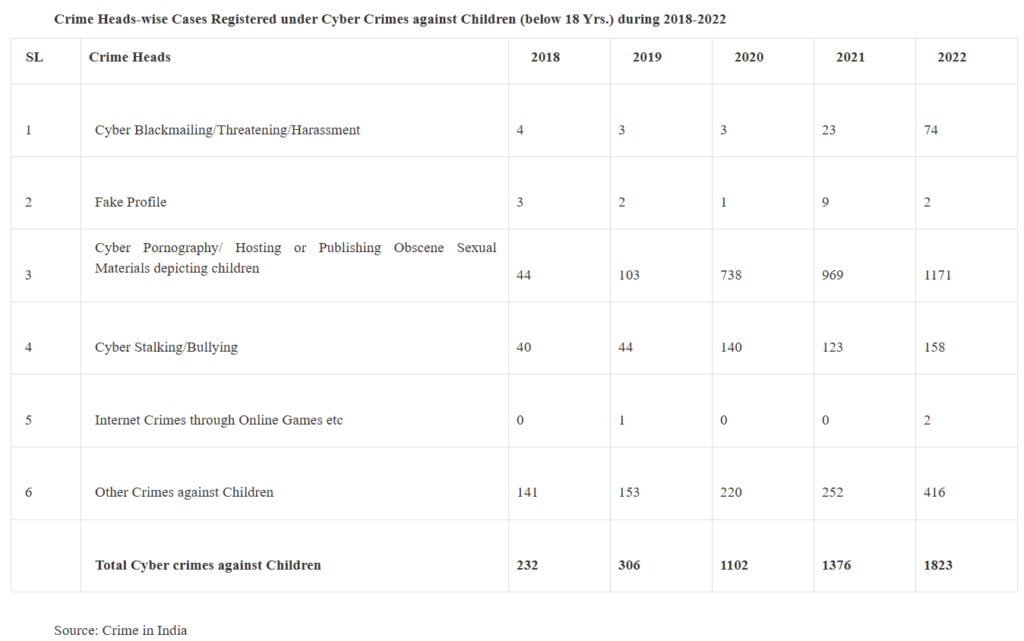

The darkest and most alarming dimension of India’s digital childhood is the exponential rise of online grooming networks and cyber-exploitation. A 2019 global report from UNICEF unequivocally warned that countries characterized by large youth populations and critically low digital literacy face the single highest risks of online grooming. Indian data chillingly validates this prognosis. National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data reveals a more than 400 percent surge in documented cybercrimes against children over the past five years alone. Predators skillfully exploit the very imagery and aesthetics that define Indian childhood, utilizing cartoon avatars, commonplace emojis, and playful filters to mimic familiarity and instantly cultivate trust. Children raised on a steady diet of animation often possess a diminished capacity to distinguish between innocent aesthetics and malicious intent. The figure of the predator and the image of the playmate terrifyingly collapse into one.

The pervasive silence surrounding this profound trauma is inherently cultural. Open, necessary conversations about sexuality, informed consent, and digital risk remain tragically rare, not due to a deficit of parental care, but because vulnerability has historically been equated with deep shame within Indian households. The emotional isolation of the Indian child is therefore structural, not accidental. Predators grasp this weakness precisely and exploit it with cold precision.

Running parallel to this exploitation is the alarming, rapid-fire commercialisation of childhood itself. India’s mushrooming child-influencer economy fundamentally transforms children into perpetual performers. Their faces, their private emotions, and their developmental milestones are mercilessly converted into content for mass public consumption. Global brands monetize their innate innocence. Parents actively curate and commodify their personalities for distant audiences of strangers. India currently operates with no legal protections whatsoever for child influencers, no enforceable working-hour limits, no mandatory financial safeguards, and absolutely no emotional protections. In this unregulated marketplace, childhood is reduced to a commodity, indifferent to its vulnerability.

None of this systemic damage can be cavalierly dismissed as a necessary cost of technological modernity. This is not progress; it is an unforgivable abdication of national duty.

Australia’s proactive ban should not inspire detached admiration in India; it must provoke a national, anguished introspection. Australia, while far from a utopia, has courageously acknowledged a fundamental truth that India persistently refuses to confront: children cannot safely coexist with digital systems engineered for compulsory addiction. India continues to frame the mounting digital harm primarily as a parenting issue or a simple discipline problem. It is none of these things. It is a catastrophic structural and national crisis that threatens the very foundation of its future.

Indian children are being systematically neurologically remodelled by the ubiquitous screen, profoundly emotionally destabilized by predatory algorithms, cognitively fragmented by chronic overstimulation, socially manipulated by sophisticated predators, and economically exploited by the rapacious influencer economy. They are forced to navigate a relentless psychological battlefield completely devoid of armour, comprehensive guidance, or institutional protection.

This profound collapse cannot be reversed merely by advising individual parents to impose arbitrary screen limits. Nor can it be substantially mitigated through abstract moral appeals to self-discipline. Childhood in the contemporary context is primarily shaped by the underlying digital infrastructures, not by good parental intentions. Algorithmic platforms are effectively raising India’s children while the state stands inertly watching from a calculated distance.

Australia took decisive action because it recognized a core truth: children lack the capacity to self-regulate in environments explicitly engineered to override that self-control. India must now recognize an even harsher truth: its children encounter these toxic environments earlier, for longer durations, and under circumstances that are profoundly more damaging and unregulated.

The critical question facing the nation is not whether India should slavishly replicate Australia’s specific law. The more profound question is whether India is finally willing to acknowledge the undeniable fact that its children inhabit a world that is neurologically, emotionally, and morally incompatible with the essential requirements of healthy childhood itself.

If the ABCD Study demonstrates the chilling reality of how screens structurally restructure the developing brain, if the Twenge research provides empirical proof of how social media fractures foundational emotional stability, if the collective evidence from UNICEF and NCRB confirms the staggering scale of online grooming and digital predation, and if the daily testimony of teachers across the country attests to the collapse of attention, then India can no longer morally or pragmatically postpone decisive action.

Childhood is not a renewable resource. Once fundamentally eroded, it cannot be rebuilt. India is not merely running out of time to act; it has, in every practical sense, already run out.

Australia’s ban stands as an unforgiving warning etched in stone. India must now choose whether it will continue its reckless policy of outsourcing childhood development to predatory algorithmic systems or whether it will reclaim this sacred responsibility through a commitment to governance, ethical responsibility, and institutional intervention.

India now stands in urgent need of fundamental structural intervention, not merely more empty rhetoric. The country requires, with absolute urgency, the establishment of a Digital Childhood Protection Commission: a robust statutory authority empowered to stringently regulate platform design, rigorously enforce mandatory age-verification, effectively restrict all forms of behavioural data extraction from minors, proactively monitor grooming patterns, and establish scientifically-backed national guidelines on appropriate screen exposure and comprehensive digital literacy. This commission must immediately collaborate with leading institutions like NIMHANS, the Indian Academy of Pediatrics, NCERT, and dedicated child-rights bodies to craft evidence-based developmental standards custom-fit for India’s unique digital generation. Without the immediate imposition of such a comprehensive framework, India will continue its tragic course of sacrificing its children’s future to systems whose core financial interests stand in direct, ethical, and developmental contradiction to children’s fundamental wellbeing.

Protecting childhood cannot, and must not, remain a silent, private burden borne solely by struggling families. It must be elevated immediately to a national responsibility, firmly anchored in developmental science, unassailable child rights, and unwavering moral clarity. Only through this total institutional mobilization can India harbour any realistic hope of rescuing what remains of its children’s formative years before the essence of childhood disappears completely and irrevocably.

(Sheikh Ayesha Islam is a Delhi-based writer who focuses on art, culture, politics, entertainment, digital discourse and broader social narratives. An alumna of the Department of Educational Studies, Faculty of Education at Jamia Millia Islamia, she holds master’s degrees in Social Work and Early Childhood Development. She can be reached at islamunofficial@gmail.com).

The views expressed in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the policy of the platform.