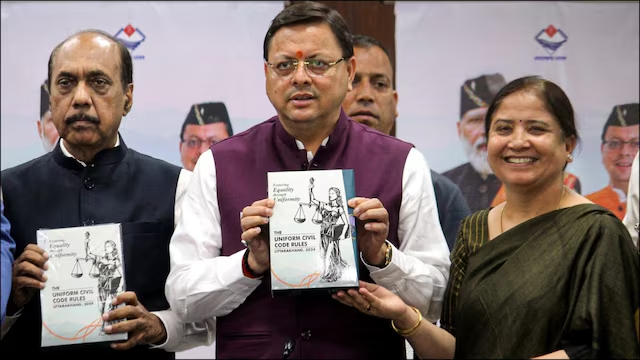

Uttarakhand has become the first Indian state to implement Uniform Civil Code (UCC), a contentious legislation aimed at unifying personal laws across religions. Chief Minister Pushkar Singh Dhami announced the implementation of UCC on Monday, January 27, hailing it as a milestone in ensuring equality across societies.

“This is our contribution to the Prime Minister’s vision of a developed and self-reliant India,” Dhami said, adding that all necessary approvals and training of officials had been completed for its rollout.

Scope of UCC in Uttarakhand

The UCC governs laws relating to marriage, divorce, succession, and live-in relationships, mandating uniformity across all religions. Key provisions include:

- Setting equal marriageable ages for men and women.

- Banning polygamy and Islamic practices like halala.

- Treating all children as legitimate, regardless of the circumstances of their birth.

- Introducing simplified procedures for creating wills and regulating live-in relationships.

Vice-Chancellor Surekha Dangwal of Doon University, who served on the composing committee, underscored the code’s emphasis on gender equality, stating, “The term illegitimate has been entirely eliminated when discussing children.”. She also emphasized the unique provisions for defense personnel, which include a flexible “privileged will” system for soldiers who are engaged in warfare.

The UCC was a major promise in the BJP’s 2022 election manifesto, which led to the party’s historic second consecutive term in Uttarakhand. Shortly after forming the government in March 2022, Dhami established an expert panel led by retired Supreme Court judge Ranjana Prakash Desai to draft the legislation.

The committee’s draft, prepared over 18 months through consultations with various communities, was submitted in February 2024. The state assembly passed the legislation on February 7, receiving presidential assent the following month. An additional committee, led by former chief secretary Shatrughna Singh, later framed the rules and regulations for the act’s implementation.

With Uttarakhand’s implementation, other BJP-ruled states, including Assam, have expressed interest in adopting similar models.

There has long been discussion on a Uniform Civil Code. Its roots can be found in the landmark Shah Bano case of 1985, in which the Supreme Court decided to grant support to a Muslim woman who had been divorced after forty-three years of marriage. The decision, which advocated for the UCC’s implementation, caused a great deal of controversy, especially among Muslims who saw it as a challenge to Shariat law.

Muslim clerics questioned the need for such payments when grown children could assist their moms and said that clauses like post-iddat maintenance violated Islamic law. Islamic law requires ex-husbands to pay for all of their children’s expenditures, including breastfeeding, until the youngsters are self-sufficient, according to critics.

Left-leaning voices initially backed the UCC as a progressive step, and the Shah Bano case became a focal point for female organizations and political bodies. But the Left has changed its position in recent years, accusing the BJP of marginalizing Muslim communities through the UCC.

The UCC’s implementation in Uttarakhand may serve as a litmus test for other states that are considering adopting legislation of a similar nature. It is yet to be seen if UCC will increase social tensions or live up to its promise of equality.