By Syed Affan

On October 30, the Home Ministry of the Chhattisgarh Government banned the Moolwasi Bachao Manch (MBM), a forum of Adivasis in the Bastar district of Chhattisgarh, opposing the Military camps, displacement due to mining and environmental degradation in the region for more than 3 years.

The circular alleged that the organization was opposing the “development” and the Military camps in the region. The ban was imposed under section 3 of the Chhattisgarh Special Public Security Act, 2005 (CSPSA).

On 8 November, 6 activists of the MBM were taken under custody at Girgunda, Chhattisgarh. These activists—Arjun Soni, Muya Hemla, Nagesh Banse, Joga Midiyam, Gillu Katam, and Bhima Kunjam—were en route to a demonstration from Nambi to Kondaphalli and had stopped in Girgundi the previous night, where they rested in the village. The following morning, police forces visited the village, and arrested them.

Raghu Midiami, president of the MBM, told The Observer Post “This ban is illegal. MBM is an open, democratic organization of Adivasis fighting to protect our ‘Jal, Jangal, Jameen’ against the development that costs our lives”.

Ehtmam Ul Haque, a member of the Forum Against Corporatization And Militarisation, a joint forum of Progressive organizations and Intellectuals based in Delhi-NCR alleged that “The MBM is an organization of Adivasi youth who lost their family members during the Salwa Judum and the operation Green hunt”.

Formed in 2021, after four people were killed in a police shooting in Silger, the Moolwasi Bachao Manch had been actively opposing the military camps which are built without legal compliance with the Panchayats (Extension to the schedule areas) Act, 1996 (PESA). The Adivasis of Bastar had been in a sit-in protest at Silger and almost 30 other protest sites in Bastar against fake encounter killings, mass arrests of Adivasi peasants and aerial bombings happening in Bastar.

Soni Sori, a prominent Adivasi activist in Bastar criticized the move, saying “If the government listened to the demands of Adivasis, stopped mining instead of killing 4 people in Silger, MBM would not have been needed.”

Anti-camp movement

Silger, a village in the Tehsil Konta of the Dantewada District began witnessing massive sit-ins, protests, and resistance at the site where the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) designated a 10-acre agricultural field for a camp in May 2021.

The land, protected under the Fifth Schedule of the Constitution, was taken without any consultation with the Adivasi inhabitants- a mandatory process mandated under the PESA Act.

Close to the Bailadila Iron ore mine, owned and operated by the National Mineral Development Corporation (NMDC), Silger was witnessing a change in its infrastructural topography, owing to the development of roads for the easy movement of the mined iron out of the region.

“The villagers started protesting at the under-constructed camp site on the night of 12 May,” recalled Ehtmam. An eight-member team including journalist Meena Kotwal, poet and activist Meena Kandasamy, and Professor Saroj Giri, constituted a fact-finding mission to Silger. “We went there to extend our Solidarity to the movement led by the Adivasis against the popular Silger massacre and to collect facts about the atrocities committed against the resisting Adivasis,” Ehtemam said.

On 13 May, the village representatives held dialogues with the CRPF officials against the construction of the camp. “The villagers were sent back and heckled by the officials, who raised concerns against the forced construction of the camp without a mandated process”, said Soni Sori.

The next day, a huge gathering of the Adivasi villagers settled in at the site, protesting against the construction of the camp. “The camp serves as an establishment meant to pave the way for the construction of the roads, a direct route to the displacement of the Adivasis”, Ehtmam Said.

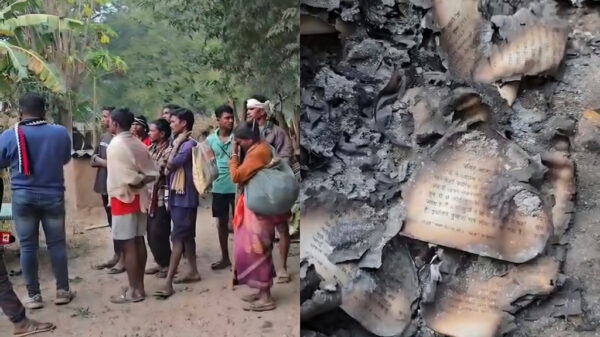

The report of the fact-finding mission laid out that on 17 May 2021, the peaceful March led by the Adivasis to the campsite witnessed confrontations between the CRPF and the Adivasis, leading to the killing of the four Adivasis– Kawasi Waghaira, Korsa Bhima, Uike Pandu. A pregnant woman, Punem Somli, succumbed to the injuries while as many as 50 people were injured.

The formation of the Moolvasi Bachao Manch

On 17 May, the bodies of all four deceased were brought to the protest site, amidst the huge gathering, demanding a judicial inquiry into the killing.

Surnderaj P, Inspector General of the police, Bastar Range, claimed that the three protestors were killed by the Maoists when the members of the outlawed party opened fire at the camp.

Subsequently, over 62 residents of the Silger village wrote a letter to the Journalists and Activists, and sought intervention from the Governor of Chattisgarh, Anusuiya Uike.

The statement said that the camp was being established under the pretext of a “farzi gram sabha” or a village council that never took place. In Adivasi areas, development projects require approval from the village council.

In the past, a local police official had assured the villagers that the camp would not be set up, the letter stated. But when this promise was flouted, the villagers decided to stage a protest. The letter sought the intervention of the governor: “Please put an immediate stop to the opening of the camp… institute an inquiry into police firing on peaceful protestors, take strict action against those guilty and deliver justice to us.”

The Moolwasi Bachao Manch was the result of the Silger episode. It was co-founded by Suneeta Pottam, the Adivasi activist who was later arrested this year in an incident which gained international attention for its nature. The Silger movement as well as many mass protests in Bastar were being spearheaded by the Mulvasi Bachao Manch.

“Too many witnesses to expose oppression”

In 2016, Suneeta Pottam along with Munni Pottam had petitioned before Chhattisgarh High Court against the “extra-judicial killings” of six persons in 2016 in the villages of Kadenar, Palnar, Korcholi and Andri of Bijapur district and enforced disappearance of Sukku Kunjam, who had gone to his paddy fields in Gangaloor Village in Bijapur district in November 2015. He was found dead the next day after the Police had carried out a search operation in which he was shot dead.

The case, filed in the High Court was later transferred to the Supreme Court and tagged with another case, Nandini Sundar and Ors v State of Chhattisgarh, better known as the Salwa Judum case, where it is still pending.

Hailing from the Korcholi Village, Suneeta had filed petitions for her safety to the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) as well as the courts. Since she filed a petition, she was allegedly branded working at the behest of the Maoists.

On 3 June, Suneeta was picked up by the police from a room rented by a Women’s Collective in central Raipur. “The Human rights activist was pursuing High school by Open School, and was staying there to prepare for an entrance test,” the People’s Union for Civil Liberties said in a statement.

As per the activists, Suneeta’s arrest was carried out in complete violation of the guidelines laid down by the Hon’ble Supreme Court in the DK Basu case, as no memo of arrest was prepared and attested by family, friends, neighbours, despite strong requests.

Condemning her arrest, Soni Soori told The Observer Post that “She was leading several ongoing protests against the widening of roads piercing through several villages, cutting hundreds of fruit-bearing trees without holding any Gram Sabha, in complete violation of the PESA Act”.

The State and Union governments have faced widespread criticism from human rights activists over allegations against MBM. “The construction of roads aims for the domination of the military camps for the forced displacement”, said Soni Sori. “The villagers do not oppose the roads, they oppose the roads which are constructed with direct legal violations without the mandatory consent of the villagers,” she said.

The consequences of a development, against the needs of the Adivasis have been a subject of contention in the resource-rich lands of Chattisgarh. “The real development of the Adivasis of Bastar underscores construction of schools, hospitals, and forests-based livelihood options,” Professor Nandini Sundar, a prominent sociologist and Human rights activist told The Observer Post.

“The government rather engages in violent means to facilitate the mining, and any resistance to it is labelled as a Maoist campaign,” Professor Nandini said.

According to the Human rights activists, there are too many witnesses to the rampant oppression and too much evidence. The government has persistently attempted to evade responsibility for its failures. Punishment is thus meted out to those who reveal facts about the state-sponsored oppression.

Human rights violation

In May 2024, a submission titled Violation of Civil and Political Rights of Indigenous Peoples in India was presented to the UN Human Rights Committee in preparation for India’s forthcoming ICCPR review. This submission was collaboratively prepared by the Forum Against Militarization and Corporatization (India), Foundation The London Story (The Netherlands), International Solidarity for Academic Freedom in India (Worldwide), India Justice Project (Germany), and the London Mining Network (UK).

The United Nations Human Rights Committee reviewed India’s fourth periodic report under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) on 15 and 16 July 2024. The resolutions, aimed at evaluating India’s compliance with its ICCPR obligations, were officially released on 2 September 2024.

The report highlighted that the Chhattisgarh Special Public Security Act (CSPSA) is widely misused to target Adivasis, activists, and human rights defenders under the pretext of countering terrorism. It enables arbitrary detentions, often without legal basis, violating Articles 9 (security and liberty) and 14 (fair trial) of the ICCPR. The law allows detention for up to three years for vaguely defined “unlawful activity,” suppressing dissent and undermining fundamental rights through prolonged pre-trial detention and unfair trials.

The report mentions the severe Human rights violations in the region due to mining operations in Adivasi lands. “It’s accompanied by militarized responses like Operation Green Hunt, leading to violence and destruction,” the report read.

Concerning the extra-judicial killings where civilians have been killed under the pretext of being Maoists, the report condemned the routine killings of the Adivasis.

On January 1, 2024, a protest was held in the Mutuvandi Village at a site where the construction of the road was being carried out. Massi Vade, a local Adivasi woman was feeding her 6-month-old child when indiscriminate firing by the security forces hit the child, piercing Vade’s hand and killing the child.

“Mangli, the young girl’s death served as a punishment to the whole village because they attempted to protect their lands, livelihood, and dignity,” Dule Vetti, a 50-year-old Adivasi woman from the village said.

So far, official reports claim that 197 people have been killed in Chhattisgarh, allegedly all Maoists in 2024. Human rights Activists say that this is a vague statistic. “The killing of Villagers is carried out under the pretext of Maoists, but Hundreds of Adivasis have been killed for their resistance,” Soni Sori said.

“Why would you ban an organization like Moolvasi Bachao Manch,” said Professor Nandini Sundar. “MBM is a collective of villagers, and so, banning it means outlawing all forms of protests so that all obstacles to mining are eradicated.”

The UN report called for repealing repressive laws like CSPSA and UAPA, ensuring fair trials, and independent probes into extrajudicial killings, sexual violence, and fake encounters. It urged the prosecution of perpetrators and emphasized implementing the Fifth Schedule, Forest Rights Act, and PESA to protect Adivasi land and governance rights.

On May 10, 2024, 12 people were killed in the Pidiya village of the Bijapur district, out of which 10 were ordinary villagers. As one of the numerous cases of extra-judicial killings, activists and villagers had refuted the police, who claimed that the “Members of the CPI (Maoist) party had mingled with the villagers”.

A fact-finding report by PUCL concluded that the encounters were fake, killing 10 ordinary villagers and 2 unarmed Maoist guerrillas. “The killing was by no means an encounter as claimed by the police but in fact a clear case of an extra-judicial killing by the security forces, where villagers engaged in their daily activities were surrounded, hunted down and shot by the police,” the report of the PUCL concluded.

“Those killed include villagers who were plucking Tendu leaves in the jungle. They started running when they saw the police and the jawans shot them. I talked to some family members of the deceased, and they told me that some of the villagers were also picked up from their houses and killed in the jungle,” said Sori, a member of the Fact-finding team.

A sustained Crisis

The Adivasi peasantry in the country has its livelihood intrinsically attached to their lands, which supports their sustenance and breeds their livelihood. The fight for the ‘Jal-Jungle-Jameen-Ijjat-Adhikar’ necessitates the protection of their rights.

Professor Saroj Giri, an assistant professor of Political Science in Delhi University and a member of FACAM, told The Observer Post that “All over the country, the Governments are serving the mining giants like Vedanta, Essar, and Jindal, companies which have credited massive amounts to the electoral bonds of the BJP and other parties.”

“Do you see anyone speaking against it?” he said. “The whole political class is behind this ongoing oppression, which is frustrated by the democratic resistance of the Adivasis and is afraid of them. Hence, it uses vague narratives to discredit the demands of the Adivasis”.

Since the intensification of the Military operations, reports of Aerial bombing have surfaced. The locals are threatened from leaving their homes, rendering them inaccessible to their farms. “The poppy fields are turning barren, the forces stop the locals and interrogate them, causing fear amongst them,” said Junas Tirkey, President of PUCL, Chattisgarh.

The first aerial bombing occurred on April 19, 2021, in Botalanka and Palagudem. The second took place on the night of April 14-15, 2022, when drones bombed Bottethong, Mettagudem, Duled, Sakler, and Pottemangi. The third bombing happened on January 11, 2023, targeting Mettaguda, Bottethong, and Erapalli, with nine bombs dropped and firing from two helicopters.

The Coordination of Democratic Rights Organisations (CDRO), a coalition of 18 civil rights groups, conducted a fact-finding mission on alleged drone-led bombings in Usoor Block on January 11, 2023. On February 1, a team of 24 activists, including lawyer Bela Bhatia and journalist Kamal Shukla, attempted to visit the affected villages. Despite notifying district authorities, the CRPF’s 150 Battalion at Dubbatota, Sukma, blocked the team, citing “security concerns” and claiming central authority. Repeatedly “harassed” at multiple camps, they were forced to abandon the mission.

On March 4, 2023, CDRO revisited the villages in Usoor Block and confirmed evidence of aerial bombings. In Mettaguda, the team observed bomb craters, remnants, and metallic shrapnel, concluding that drones dropped nine bombs on January 11, 2023, followed by helicopter gunfire targeting Adivasi villagers.

Villagers had previously protested these bombings, but officials offered contradictory responses. While CRPF IG Saket Kumar Singh, in an interview with Scroll, admitted to firing from a helicopter in “self-defence” after being allegedly attacked, Bastar police denied any aerial bombing.

“These bombings, particularly the bombing of 11th January 2023 in Usoor Block, whose fact and existence have been directly ascertained by the fact-finding team, clearly violate various international laws and covenants to which India is a signatory state. However, it is very concerning that the state itself is bombing its citizens”, the report stated.

In a video shared by the Bastar Talkies, hundreds of villagers of the Bijapur district were seen protesting against the aerial bombing which occurred on 7 April 2023. The European Parliament, in its Parliamentary question, raised concerns and alleged that it was the fourth such bombing in the region.

The conflict in the region intensifies, with significant threats to Adivasi cultural and social life. Human rights activists criticize the government for suppressing avenues of democratic struggle, further neglecting the need to negotiate with the locals whose rights are protected under the Fifth schedule of the constitution.

Kaladas Dehariya, Secretary of the Chattisgarh PUCL, said that the movement in Bastar wasn’t anti-development, rather it was anti-mining protests. “Wo Vikaas chaiye jo logon ko zindagi de, na ki unki jaan le le”, he said, demanding the revocation of the ban on the organization.

(Syed Affan is a writer and independent journalist based in Delhi. His reportage focuses on human rights, state repression, and violence engendered upon communities in resistance.)