A week ago, Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched a massive ₹26,000 crore project package in Bikaner, Rajasthan. Speaking at the event, he said, “Today, the amount spent by the nation on these infrastructural developments is six times what was used before.” He also highlighted that in the past 11 years, major progress has been made in modernising roads and railways, including the inauguration of 102 redeveloped railway stations across 18 states.

Yet, even as the country pushes ahead with big development projects, the harsh reality of sanitation workers remains unchanged. From cleaning dry toilets to suffocating in 10-foot-deep sewers, many continue to face dangerous, inhumane conditions — a problem that has seen little relief despite manual scavenging being illegal in India.

On Monday, six workers in Bikaner lost their lives inside a jewellery factory’s sewage tank. The management had forced them to climb deep into the tank to collect chemical sludge, claiming it contained gold and silver particles from the manufacturing process. Although the workers were hesitant at first, they were lured with promises of extra pay. Two of them went in first, and when they began to suffocate, four others rushed in to save them — but tragically, all six died inside.

This tragedy comes despite the Prohibition of Employment of Manual Scavengers and Their Rehabilitation Act, passed by the Indian Parliament on September 6, 2013. Since March 27, 2014, manual scavenging has not only been illegal, but caste-based discrimination and the abuse linked to it are also under judicial review. The law makes state governments responsible for preventing this practice and ensuring rehabilitation, yet such deadly incidents continue.

More than a decade after the 2013 law banning manual scavenging, the harsh reality remains: Dalit and marginalized communities are still being forced into this dangerous, illegal work, and the system has failed to stop it.

Just recently, in Kolkata, three men died when a drain pipe burst while they were cleaning it — the work was assigned by the Kolkata Metropolitan Development Authority. On the same day, in Narela, Delhi, two more workers died after a private contractor sent them into a toxic tank without any protective gear.

According to reports by The Mooknayak, at least 20 sanitation workers have died between February and May this year across states like Madhya Pradesh, Delhi, and Tamil Nadu, highlighting the continuing human cost of this ignored crisis.

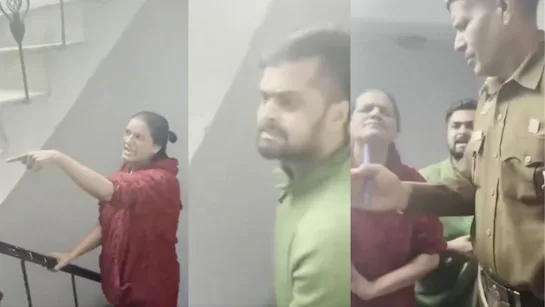

A 2014 report by Human Rights Watch (HRW) gathered powerful testimonies from sanitation workers, many of them women, who shared how they were forced to clean up to 20 toilets a day with their bare hands — and were often paid not in cash, but with leftover food. Workers said they faced threats from employers if they tried to quit, and all this happened openly, with full knowledge of the villagers around them.

“I have to go. If I miss a single day, I am threatened,” one worker told HRW.

The report exposes a deep, systemic oppression of Dalit and marginalized communities, using them as invisible shields to perform the most degrading work — while keeping them outside the reach of the legal protections meant to uphold their rights.