The Bhagalpur riots of 1989, which saw over a thousand people, mostly Muslims, brutally murdered, have long been forgotten in the annals of history, overshadowed by larger, more politically significant events like the 1984 anti-Sikh riots and the 1992-93 Mumbai riots. Yet, for the families torn apart by the violence, justice remains a distant hope.

On the morning of October 24, 1989, a Ramlila procession, en route to Ayodhya, passed through the Gaushala area in Bhagalpur. As it reached the predominantly Muslim locality of Tatarpur, the procession turned violent, with participants hurling provocative slogans such as “Mullah Bhago Pakistan” and “Baccha Baccha Ram ka, baaki sab haraam ka” (Every child is Ram’s, the rest are illegitimate).

Tensions escalated, and amid the confusion, crude bombs were thrown at the procession, injuring several policemen. This incident triggered the violence that would soon engulf Bhagalpur and its surrounding villages.

More than 250 villages were set ablaze and thousands of people, mostly Muslims, were massacred. Official figures put the death toll at about 1,000, but independent estimates put the number much higher. According to the People’s Union for Democratic Rights (PUDR), 93% of the victims were Muslims.

By the time the violence subsided, the official death toll stood at 1,070, although independent estimates suggest that the actual number of deaths was much higher. Over 11,500 houses were destroyed, displacing nearly 50,000 people, most of them Muslims. The Bhagalpur silk industry, which was primarily Muslim-owned, was decimated, leading to significant economic losses for the community.

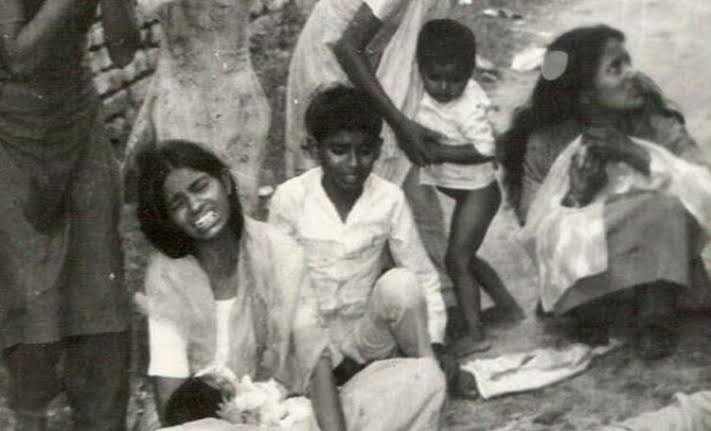

The Bhagalpur riots stand out not only for their scale but also for the institutional failures that followed. In the worst-hit areas, such as Parbatty in Bhagalpur town in eastern Bihar, there were wells full of mutilated bodies, which the local press quickly announced were those of Hindu students killed by Muslim mobs. But they eventually turned out to be the family of Muslim man Mohamed Javed, all 12 of them.

The 1995 Riots Commission of Inquiry, which investigated the Bhagalpur riots, squarely blamed the local administration, police, and media for their role in spreading misinformation and failing to protect Muslim Community. The Commission also indicted the Congress-led state government for its failure to maintain law and order, a pattern that would be repeated during the Mumbai riots in 1992-93.

Mallika Begum (image-below) is one of the survivors of the Bhagalpur riots and was only 14 years old when she testified before the Patna High Court.

She lost her right leg in the incident in which villagers were paraded by the mob, cornered from all sides, and systematically killed. They didn’t hate us,” she says, ”they hated all Muslims.

Kapildev Mandal (image-below) was a witness before the Commission of Inquiry and testified that the procession was led by a right-wing Hindu group armed with swords, sticks, spears, and farsans. Kapil Dev still defends his testimony today, reiterating that they were shouting slogans like Baccha baccha Ram ka, baki sab haram ka).

According to several media reports, on the Hindu side of Parvatti today there is an apparent construction boom (see image) on land and houses that once belonged to Muslim families.

Despite the scale of the carnage, Bhagalpur has largely faded from the national consciousness. In 1990, reports were already calling it the “forgotten riot,” overshadowed by the political upheavals of the time. The Lalu Prasad Yadav government in Bihar, preoccupied with anti-reservation agitations, did little to address the concerns of the survivors.

Even in subsequent years, Bhagalpur only resurfaced in political discourse around election time, with promises of justice and compensation that were rarely fulfilled.

In 2005, Chief Minister Nitish Kumar set up a new commission of inquiry under Justice N.N. Singh. The commission’s report, submitted in 2013, recommended action against 125 IAS and IPS officers and indicted the Congress government for its failure to prevent the violence. However, the recommendations have largely remained on paper, with many of the perpetrators still roaming free.